Ten Years Later at the Gardner Museum

When I first began thinking about Isabella Gardner and the museum, I found the place both beautiful and frustrating—as if frozen in time. And then when I began reading biographies of her they too seemed frozen in the times they were written. Also, I was beginning with an Isabella who did not seem so compatible. She was flamboyant and fun, but also guarded and discreet. The museum is her legacy to us, but it’s also the location where controlled gossip about her can go on.

Writing history, however, is a way of creating a compatible world, and I wanted to write about her and her time in a way that wasn’t trying to be authoritative, but was just true to my own purposes. So, I went back to things written by her friends, to old letters, and to other stories about her friends…there were many tangents, and I have a tendency to digression. All this meant that my own reflections would be part of the story–that her story, or the history of her Boston, or of the experience of women, or of her friendship with Buddhist philosophy, or of the art itself would indeed come from the places where they caught my interest.

When you go through the museum today it feels to me as if it calls for a different response from when I wrote the book. Now you come into the museum through a beautiful example of contemporary museum architecture. The addition by Renzo Piano says very clearly that this is something for our time, and it does in its own way what Isabella Gardner was doing a little over a century ago: it makes the whole museum into an artwork itself.

Now you no longer enter the museum beneath the shield over the entrance on the Fenway declaring the place the creation of her will and pleasure; instead, after being welcomed in a bright and open 21st century space, you are led through a glass tunnel into the past. This means you don’t come into her creation simply as a museum with pictures and other art objects, but as a grand art object itself. I think it was always that in a way, but now it’s truly presented as a whole. It’s an aesthetic experience that isn’t gauged by its individual artworks or how accessibly arranged they are. Now the old museum also takes some of its feeling from the new addition—it feels much more open now than it did, better lit, more welcoming, very spruced up. It feels more loved, actually.

In the course of the twentieth century it fell on some hard times. When the book first came out, people would tell me they remembered the museum when it was so quiet it was a good place to study, when you could hang out there with the guards. That wasn’t the case of course when I wrote the book, but it still had a slightly eccentric feeling. There was always the pleasure of coming into the courtyard and of circling it on the different floors as you toured the rooms, but it often felt as if there were a lot of dim corners—as if there were things no one had looked at in a long time. Since Isabella had stipulated that nothing could be removed or moved from the way she’d arranged them, the place had a touch of Miss Havisham to it. Why this here? And why is that hung so I can’t actually see it properly? It doesn’t feel like that anymore. It feels much more lived in now, a place for our time as well as hers.

Isabella didn’t actually know what it would mean to have people trailing through her house, looking at her things, and sometimes picking them up. She wanted to bring a more European sensibility to America, to share and show off what had meant so much to her life. Doing that is always a little double-edged: it brings into surprisingly close quarters things formerly separated by class and custom and wealth and sensibility. I think that when I wrote the book the discomfort of that still lingered, despite the many ways it had evolved since its opening on New Years Day 1903.

Even in this new, bright, open, twenty-first century iteration, there is still that museum, and its traces of the long ago Isabella, a wealthy society woman who was perfectly happy to be talked about in the newspapers. And there is still me, with my hodge-podge of opinions and an attitude toward art museums that has always included a defiant little movement of refusal, an internal gesture maybe left over from childhood, but also something about the very nature of museums. They are there to guard the art as well as display it.

What you want in a museum is a relationship with the art. That is, there’s a threshold moment when you have to face being a bit of an outsider. Will this place open up for me? Can I be free here? Will I find something I can genuinely connect with? Or will I just feel stupid?

Paradoxically this museum, with its welcoming courtyard and beautiful rooms, can make it harder to be intimate with the art. It’s quite different from an institution like the Museum of Fine Arts or the Metropolitan Museum, but maybe even more than with those is the danger of being just a tourist.

In writing the book I set out to get over that–I was writing a sort of anti-biography, and my research was both serendipitous and purposeful. I had no idea how it would fit together; it was only very late in the process that I saw I could break it up into sections, and then that those sections could take their titles from the things in the museum. This made the story of my coming closer to the past and to Isabella and to the art seem a kind of tour of the museum, even though it is not.

Following my nose in her world led me to her very interesting friends, to old scandals and battles, to a love affair and some dreadful novels, to witty letters and afternoons in Paris or Venice. It led me finally to Japan and the Far East, and its philosophical influence back home. All this history finally led me to my own side tunnel into the distant world from which the museum comes to us.

The first was her friendship with Okakura Kakuzo, the sophisticated, cosmopolitan Japanese curator of the newly established Asian collection at the Museum of Fine Art. Okakura’s Book of Tea is a little work of art that brings an eastern philosophy of imperfection, incompleteness, and impermanence into an American world of striving for exactly the opposite. And yet it offers a way of living with the world of American (and European) too-muchness that the museum also exemplifies.

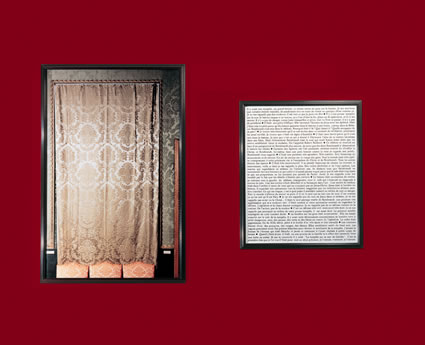

The second was the famous theft—a violation of both her will and the protective veneration of art all museums imply. It was shocking and heartbreaking and it also put the museum in the news. It was now an emblem of how impossible indeed is the idea of permanence. As I wrote the book, though, I was inspired by a project from the French artist Sophie Calle called Last Seen… Calle used the very missingness of the stolen paintings to make a new artwork that recreates them in the words of the museum staff who remembered them. And then she put a collage of these different descriptions together in a frame, and set them beside photographs of the empty picture frames, offering language and memory alongside the loss. It’s an artwork about intimacy with art, even as the art itself has vanished.

Work like this is another kind of addition to the museum, a different way of entry that frees me to shake off her will and wander as I please through the indefinite versions of her life story, to move within the frame left empty by her death and make the place my own.