Three Excerpts from

The Real Life of the Parthenon

A TALISMAN OF IMAGINATION

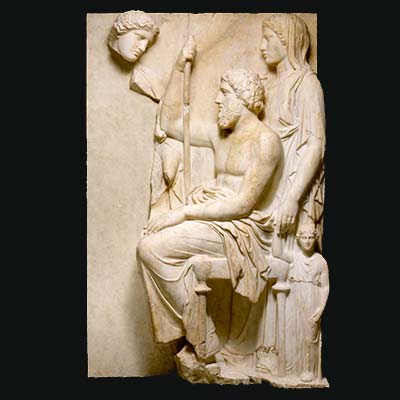

Later in the afternoon I was standing before a marble grave stele on which a family group was shown in relief: a seated man, a woman standing behind him holding the hand of a small girl, and above them to the left the head of another woman, anchored in place but bodiless thanks to unknown events in the course of time.

Here the commentary was wordless: it came only as a visual effect of the display, which subtly continued to establish a new context without any language at all. This image of family stillness and affection was placed beside a huge window so that the light falling on the stone continued the sculptor’s work, gently shaping its curves and losses. It was another fruit from the cornucopia of the Rogers Fund, but questions of how it got here or where it came from now seemed of less account than the aesthetic resonance of its current installation. It was fresh and touching; even its brokenness drew me closer.

I had seen rooms at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens full of similar graven families bidding farewell to their loved one. Those assembled fragments had been testimony from the local past, from the vast treasury of the local earth: an archive perhaps of local meaning. This one, however, brought to New York City in 1911, is presented so that part of its meaning now emerges from the open sky over Fifth Avenue, the sky that covers the earth everywhere. In this context it seemed the loss it commemorates is unspecific and ongoing: of civilizations, of all monuments and materials, of skillful artists, of time slipping silently past as the light from the window changes.

I glanced out at the high buildings across the way, one decorated with Renaissance-style stone garlands, the other with triangular pediments or arches over the windows of one floor. Form so clearly irrelevant to function! I thought, amused at the hodgepodge architecture of the high-rent district that surrounds the museum. This was indeed a different face of empire, with everyday aesthetics casually cadged from the ancient ruinscapes. The classically embellished wealth of the city that had made possible my relationship with the grave stele was suddenly sharing the marble’s mute testimony to history.

Much like Lord Elgin’s resited collection, the things in this place and in this light seem deeply rooted in their new context, speaking less of national identity than of human creativity itself. This effect is one mission of museums like the Met: to show us the universal humanity in beauty and to recapture what has been lost. So far from home, the sculpted objects here nevertheless brought me into their mythic history, into the immediacy of antique Greece, Parthenon and all. Yet now I was aware that this lovely new context raises other questions, questions about what may have been sacrificed for this imaginative partnership.

HIDDEN IN PLAIN SIGHT

I’d set out the next day to see the remains of a temple to Poseidon at Cape Sounion, a day trip out of Athens by land along the coast to the tip of the Attic peninsula. On a crag sixty- five meters above the Aegean, it’s on the spot from which King Aegeus, mistakenly believing his son Theseus had been killed on Crete by the Minotaur, threw himself into the sea. Place me on Sunium’s marbled steep, sang Byron, ready to die for the cause of Greek freedom from Ottoman slavery.

Poseidon, says Vincent Scully, was not only the particular god of sailors and the sea, but also of horsemen and horsemanship. Feared as the embodiment of nature’s violence, he also embodied “the godlike sense of movement and command” felt by horseman and tillerman—the feel of rolling earth and sea, the consent of nature to human will. Poseidon was a god of major challenge to courage, especially the courage to move about the earth. The remains of the temple make this place more than a site of spectacular natural beauty. Yes, the land itself is a force; but here, as on the Acropolis, was asserted once again human willingness to entangle with anything.

Sitting beside the temple with the October sun hot on my arms and hard on the heavy blocks that formed the lintels above me, I’d thought the power the gods represent still offers a challenge exhilarating to tangle with. But where was the place of that challenge in my own time and place? It was not at the Getty Villa, or in Stillman’s brooding American presence on the Acropolis. Instead, here at the edge of Attica, I’d found myself thinking of a decommissioned army base in the also dramatic landscape of west Texas. I was thinking of the earth and sky of my vast and varied America, and of the Modernist artist Donald Judd.

Judd’s claims for the art of his time were Periclean; the confined interior spaces of museum galleries, with their regularly shifting displays, he found unworthy of that matchless art. “Somewhere,” he said, “a portion of contemporary art has to exist as an example of what the art and its context were meant to be.” To that end he transformed two former artillery sheds on the old military base: now floor-to-ceiling glass siding opens the space to display a hundred milled aluminum boxes, an intoxicating deployment of geometry, perspective, and the use of desert light. Human skill there too embodies a willingness to entangle oneself with anything, and the consent of nature to human will.

We’re still at it, engaging the hard-wrought facts of creation so as to entangle the present in a myth-infused heroism. The American structures at the Chinati Foundation in Marfa, Texas, are not replicating anything from elsewhere. Here, now, they say, time can be held and dismissed; as seems the case also at Sounion. This fragmented temple by the sea is also an unmovable example of the art of one time.

As the afternoon wore on and the shadows began to lengthen, a busload of French tourists arrived, exclaiming about the site and trying to make sense of the temple. One of them had a guide- book that explained who Poseidon was: “le dieu de la mer,” she read to her companions.

“Je voulais savoir . . . ,” grumbled a big-bellied man in a brand new baseball cap printed with the word GREECE. He’d like to know what he’s doing here in the warm October afternoon beside this pile of broken rock. Democratic barbarism, I’d thought (not entirely without satisfaction), is not limited to Americans.

The later Greek world of the Hellenistic age, says Jacob Burckhardt, lost the great vista of earth and temple, that promise of love between mortals and immortals. In the wake of the Peloponnesian wars came some of the darker aspects of democracy predicted by Plato, including an addiction to chatter and a citizenry living for the desire of the moment. “The democratic state, in its thirst for liberty, wanders into disreputable bars and gets drunk on too much undiluted wine,” as Burckhardt presents Plato’s point.

In a situation like this, the ancient philosopher noted, rulers and parents lose their authority, old men try to make the young laugh, the very animals go about freely, and people become extremely irritable, resentful, disconnected, and all too likely to top their ignorance with ridiculous caps. The god of the sea, le dieu de la mer, of storms and wild manes, of triremes and stamping hooves, can hardly be imagined.

Below us on the Sounion headland la mer itself stretched green and blue and full of light; a few fallen column drums lay on the beach. When the sun slipped behind the western clouds their rims and edges were suddenly backlit, and as the air cooled, a thousand seagulls swept from the undercliff into the sky, wheeling above water, rocks, temple, and tourists. We are here, Monsieur, for the ravishing Attic coastline, for its marble memory of the ancient world, this broken temple like a dream half remembered, the distant cries and rhythmic stroke of oars. The connection between myth and history is asserted here by this boundary between sea and sky. We come to be with the uncertainties, mysteries, and doubts that are the legacy of the past. We come to be with past time in its own place.

Here is where we meet antiquity on its own ground, but without the crumbled and commanding beauty of the temple would that history even matter? The continuing god-favored existence of this past is still asserted by its art. Is its landscape inextricably part of that beauty?

EDGE AND POINT

In the early California morning the warming sun slants through the arched railing around the belvedere at the Getty Villa; the sky over the roof tiles seems impossibly blue, as if I were in a glossy photograph. The sudden motion of a Red Admiral butterfly shifted my attention. In the garden tiny buds were showing on the January peach, and small mounds of catmint, oregano, germander, and sweet violet poked up around other leafless trees. Three high palm trees whispered Egypt, but the gardeners working above on the slope were singing in Spanish. In the Temple of Herakles just off the inner peristyle of the Villa, a young woman named Amber, from the Villa’s Education Department, was introducing a group of visitors to a first-century Roman sculpture of Leda and the Swan.

Amber had several points to make, including that the head was not in fact original to this Leda, but probably a head of some Venus found nearby when the statue was unearthed in 1775. At the end she read from a folder she was carrying the first stanza of “Leda and the Swan” by William Butler Yeats. When she offered to answer questions, there was only one: “How much did Mr. Getty pay for this?” a man asked.

Impervious even to the cross-species rape, the questioner was cutting directly to the wealth and power that set the sculpture just here. Amber’s mission, to embed the beauty and luxury in context, and to show a history of aesthetic fumbling toward the past, had missed its mark. At the end of the day, though, I joined a much smaller group led by a Getty curator into a room where the track to the past had been more carefully defined.

A handsome, though headless, young man, standing with his weight on one leg and draped to display his naked, one-armed beauty, had come from the Dresden State Museum in over 150 pieces, some large, some just small fragments. Some of the conservation research that had gone into this reassembly surrounded it: a marble head of Athena that had been a second-century solution to the decapitation; an eighteenth-century engraving of the statue now topped by a head of Alexander the Great. Floating in its own case like a Damian Hirst shark was a right arm: an earlier but now rejected restoration.

The meat of the conversation now was in the craft of the statue’s reassembly, both ancient and modern. How it had been originally carved in two interlocking pieces, the join concealed by the drapery folds. How the current version had added a right knee, so the pose now made sense. How the left arm and parts of the torso had been filled in, but the new additions had been left obvious, in case future conservation science needed to correct the work just done. The present was imagining its own fallibility, honoring indeed the unknown future.

Finally we were shown a paper fragment, a scrap that had been used to stuff a hole in the course of a previous restoration. It turned out to be a page from an eighteenth-century medical textbook, and simply Googling a couple of its phrases had brought the whole book up online! The coda to this exhibit was the thrill of accessible knowledge itself.

Briefly part of this small community of curiosity, I noted how we reach back toward the past, stumbling upon sources of delight: matching fragments, light on stone, mythical horror, massed columns. Here the pleasure of restoring balance and harmony, there the bingo moment when Google delivers the goods. The ancient world was in ongoing collaboration with the present, like Yeats making the myth of Leda forever his, and ours.

We talk about these things because it is pleasurable to do so, writes Michael Baxendall: “It is the impossibility of firm knowledge that gives inferential criticism its edge and point.” At this moment it seemed I was drawn to the antique objects not to assume a heritage of beauty or power, but for their irresistible unwholeness, for our inability to know for sure, the field left open for conversation and unexpected encounters. With rage and greed, with intelligence and pride, with self-centered distortion, with generosity and love, the present struggles to know the past and to put itself in the story.