Four Excerpts from Possibility

EGGS

Peter is trying to figure out how to create a structure in which to drop an egg from a fourth story window without breaking it. His favorite plan so far involves two frisbees, some bubble wrap, and a complicated arrangement of springs to absorb the impact of the fall. The frisbees (or frizbes, as he spells it) is the part of it I’d never have thought of. They make a curious clamshell ovoid and they are only part of the reason I find this project hard to relate to. Why would you want to drop an egg from four floors up if the point wasn’t precisely to see it smash? On the other hand, Peter is excited about solving the problem and has a whole page of mock-ups, including a key to understanding the materials–springs, tape, frizbe–so I am giving this my attention.

What makes an egg crack, says Peter, is that when the bottom of it hits the ground the top is still falling. He showed me with his hands. Later that night I wake up crying out in terror, in protest. I’ve been dreaming I was in an elevator full of people that was descending way too fast. Faster and faster, in fact. Having now developed some interest in the issues of how to lessen the impact of an illogical fall, I was at first scheming to hang my legs over the handrail running around the walls so that when the elevator hit, my body wouldn’t crash into itself. I heard once about a woman who saved herself in a similar situation by grabbing onto the molding at the top so she was off the floor on impact. But the other people in the elevator are screaming and, now hanging in a contorted position with one leg over the rail and no faith in the physics of what may or may not happen, I want to join them. Now, my desire is to do what the others are doing: to cry out in protest, to go down screaming for help with my fellow travelers.

What about just hard-boiling the egg? I asked Peter, but he said no, it had to be a raw egg. There’s an old story about Columbus and a hard-boiled egg–he figured out you could make an egg stand upright if you simply hard-boil it first and crack one end, thus confounding a room full of smart fellows who were for some reason confronted with this problem. Possibly this is only a metaphor to demonstrate the kind of out-of-the-box thinking needed to discover America. Five centuries later the box has been replaced by a couple of frizbes but the setting of pointless riddles about eggs to particularly intelligent people retains its appeal. I think the art of boiling an egg, while perhaps entirely off-message and perfectly unspectacular, is nevertheless a useful application of physical principles. When you finish knocking their socks off or exploring the collapsing enclosures of your own psyche, you can peel it and eat it for breakfast.

FROM

THE TASK OF THE TRANSLATOR

Vermeer had daughters, many daughters. One of them is looking out of the darkness behind her in Study of a Young Woman, her face bare and a little unsettling. She’s not the famous girl with the pearl earring, although she is wearing one and her head is turned just the same way. Her face is luminous the way Vermeer does that thing with light. The paint is covered with tiny cracks all over in a pattern that defies representation. On the surface, that is, time is showing like a veil over the timeless, mysterious youngness of her open eyes and quiet pale mouth. She could disappear into the darkness behind her…but she hasn’t. Right now she is in this room where I am standing on the edge between her world and mine.

FROM

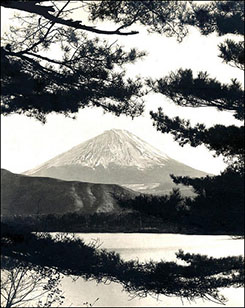

HENRY ADAMS IN JAPAN

Henry Adams did not see the point of Japan. It seemed to him infinitely childish–the whole show is of the nursery, he said, and nothing is serious. It was very hot in the summer of 1886, when he spent three months there with the painter John La Farge. Japan is the place to perspire, he wrote to his closest friend John Hay. The food was awful, the smells worse. Even the tea was dreadful, although the tea ceremony itself he suggested was the only serious labor of Japanese life. This observation notwithstanding, he bypassed the opportunity to acquire a book which contained paintings showing fifty arrangements of the charcoal to boil the kettle on this occasion; and as many more of the ways in which a single flower might be set in a porcelain stand. The whisper of sarcasm indicating the Japanese concentration on aesthetics was in fact absurd.

La Farge, on the other hand, found the Japanese sensitivity to the world’s beauties “much more delicate and complex and contemplative, and at the same time more natural, than ours has ever been.” In the heat shimmering over the flooded rice fields, La Farge saw a crane “spread a shining wing and [sink] again”; he saw the pink lotus flowers standing up in the ditches. An early letter conveys dispassionately the information that manuring the fields taints the drinking water, shortening life. Only when they arrive at their overnight accommodations on the journey from Tokyo to Nikko does he get a touch more personal: “inexpressibly outrageous” is the odor on the entry floor; “evidently of the same nature as that of the rice fields,” he adds, informatively.

Every house is a cess-pool, was Adams’s version. The surrounding country is one vast, submerged rice-field, saturated with the human excrement of many generations of Japanese. The vigorous disgust cuts through earlier ironic responses to the country, e.g., reporting himself pleased to be relieved of the fear that he’d lost his sense of smell by the oily, sickish, slightly fetid odor they found pervasive in Japan.

The upper rooms at their wayside inn, however, seemed clean and airy, although the furnishings rather bare by western standards. Even so, the night proved hideous. After a meal they concocted of canned Mulligatawny soup and boiled rice, Adams suffered an intestinal attack. He calls it cholera (an outbreak of which they were fleeing from Tokyo to the mountains), which does give an idea of what it felt like. In the morning he learned that La Farge had had a similar night. We have never found out what upset us (it was not, of course, cholera), he says, but he also notes that in their common suffering he was reduced to laughing at La Farge’s comments to a point where exhaustion became humorous. La Farge turned their wretchedness into laughter.

FROM

INVENTING CINEMA

The beautiful teenage Gish sisters show up in the Bronx on a summer morning in 1912 looking for their friend Gladys Smith who is working at the Biograph film studio. They want to be actresses on the stage, but they are currently between engagements. Gladys is already a successful actress herself, renamed Mary Pickford by the theater impresario David Belasco, and she’s been slumming very successfully in the movies for three years and she is delighted to see the Gish girls and their mother (with them, of course). She introduces them to her director, D.W. Griffith, who enters this scene singing La ci darem…a fragment from a Mozart opera. Biograph has built a new studio that even though it is in New York City is wonderfully lit by both natural and artificial light, but Lillian Gish, Griffith notices, seems to have a luminous glow around her that did not come from the skylight. Furthermore he thinks she and her sister sitting together on a bench are as pretty a picture as he’s ever seen and, being a dealer in such pretty pictures, he takes them upstairs for a screen test in which they are terrified by burglars and Griffith fires off a revolver he happened to have in his pocket. Their fright is convincing, and the next day they become the stars of a one-reeler.

Close up: a tin plate covering an empty stovepipe hole is slowly pushed away, and from the darkness the nose of a handgun pokes toward the audience. Medium shot: the beautiful teenage Gish sisters cower in a corner of the room, their matching striped dresses and soft, light-filled hair making them appear each other’s doubles. Innocence is horribly threatened because in the next room an untidy female family retainer (The Slattern Maid, according to the intertitle) has arranged for an old friend to blow up the safe in which the girls’ slender inheritance from their recently dead father is stored. In a moment, though, one of them will grope her way to the primitive telephone and call her brother, who has gone off to work on his bicycle.

The Slattern Maid has been enjoying the adventure, and has been refreshing herself with a handy pint of hooch; as the brother is hearing the plea for help he also hears the exuberant gun in her hand go off. Crosscutting: the puff of smoke from the gun; close up of the brother’s face contorting with horror. He has a small mustache and is still wearing his derby hat. Electrified, he leaves his modest bike leaning against the outside wall of his office (the clips that kept his trousers from tangling with the chain still neatly hung on the crossbar) and commandeers a motorcar. With him, now equally alarmed, are: a coworker, the chauffeur, and the owner of the car (who rushed into the frame as the commandeering was occurring).

Long shot: the men, hanging on to their hats in the open coupe, race along the country road. Cut: the girls in their lovely fear are clutching their angelic faces. Time elongates: the car races onto a drawbridge just as it’s slowly turning to cut off the route. The four men leap from the car, gesticulate at the bridge keepers.

Back at the house the safecracker produces clouds of billowing smoke. The crosscutting seems like real life, better than real life, here and there happening at the same time. We are seeing the sorry truth of crime even in the simple lives of two orphaned girls and also the heroic speed of the American automobile, which will arrive just in time. The Slattern Maid, her arm thrust through the stove hole up to the shoulder, gleefully waggles the weapon in her hand. La ci darem la mano, la mi dirai di si…Ah just give me your sweet hand. We are caught in the rhythm of rescue, which is also the rhythm of morality, and the rhythm of seduction. Ah fuggi il traditor–the flight from evil is accomplished; Don Giovanni’s song is no less sweet when enfolded into a happy ending.